- Joined

- Jan 6, 2013

- Messages

- 5,564

- Reaction score

- 11,189

1. The History

Cwm Machno quarry (also known as Cwm Penmachno Quarry) is located to the south-west of Betws-y-coed, at the head of the valley of the Machno, a tributary of the Conwy river, in North Wales. The nineteenth-century slate quarry was worked between 1818 and 1962. Initially slate was extracted in an ad-hoc manner by the locals but in 1849, serious development took place to allow wholesale extraction of slate.

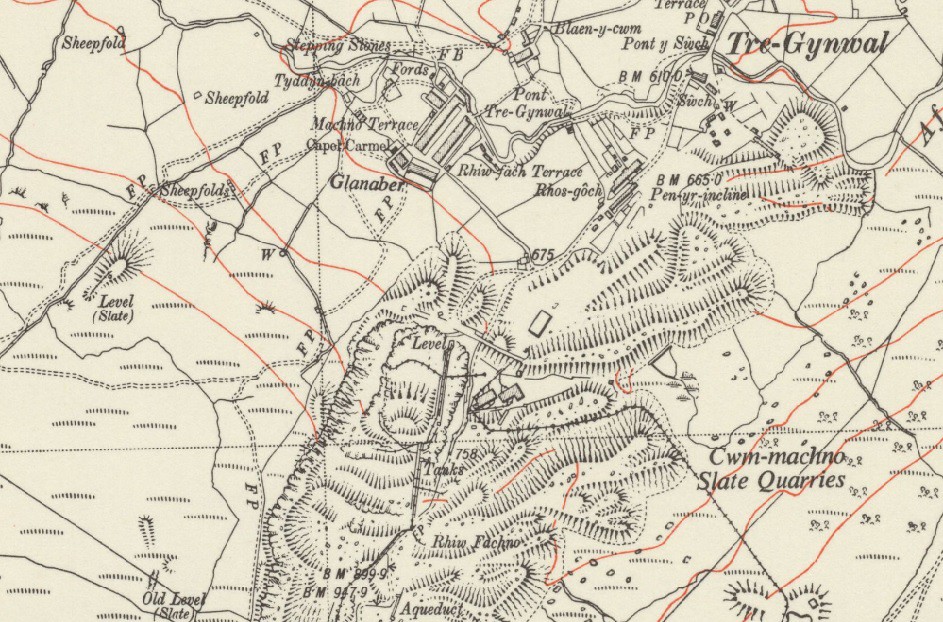

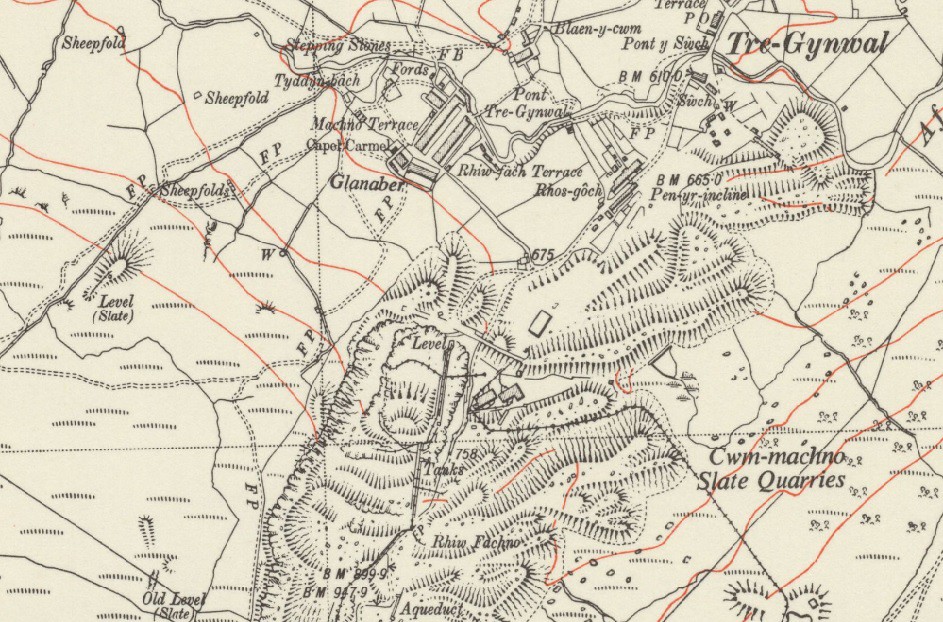

Early O/S map of the quarry workings:

Slate was worked from an open quarry on several levels, and, additionally, slate was also extracted from underground. There were originally two pits, the upper working was known as Rhiw Fachno and the lower one was the main Cwm Machno quarry. Adits led into the mountain from both pits to access the underground workings. Inclines were used to link the terraces and workshops of quarries. It was particularly noteworthy for its water-wheel that enabled both the lowering blocks to the mills as well as being able to draw blocks and rubble from the underground workings.

Transport was always a major issue. Initially, slate was taken by horse-and-cart to a wharf on the River Conwy at Trefriw. From the late 1830’s, it was carted south to Maentwrog via Cwm Teigl and on to the Afon Dwyryd to Porthmadog. Then, in 1868, the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) opened their line to Betws-y-Coed and from then onwards slate could be hauled there, however this was still a distance of 11 km over rough mountain roads. With the completion of the Rhiwbach tramway in 1863 this allowed some of the slate to be hauled up to Rhiwbach Quarry and taken out to Blaenau Ffestiniog via the tramway

The quarry also suffered from a lack of waste tipping space. Its height on the mountain meant it had a relatively restricted water supply, and on several occasions work stopped due to drought, including in 1891. The quarry became a major employer, with the workforce rising from 70 men in 1872 to 178 at its peak in 1898, before dropping 108 in 1937-8. A community developed around it with houses for the married workers along with barracks for those that were unmarried. Output peaked in 1869 with production of 8,000 tons. However, by 1890, this had dropped to just 2,260 tons.

View of Penmachno quarry circa 1875, showing the northern mill:

2. The Explore

This place tends to get overlooked, due to the close proximity of the underground delights of Rhiwbach slate mine and, of course, the many mines of nearby Blaenau Ffestiniog. However, having seen the sheer size of the waste tips on Google Maps, thought that this was well worth a morning’s hike. As it transpired, it was time well spent. The main incline was a sight to behold and there were some really nice winding houses too. So not as spectacular as its neighbours but well worth a look if you have the time. The road trip over to Penmachno from Blaenau is interesting too!

3. The Pictures

Retaining wall at the bottom of the quarry:

One of the few quarry buildings still standing:

And its resident:

Inclines to the right:

Bottom of the big incline:

The long miner’s path to the top:

Slate waste as far as the eye can see:

Some of the original piping:

Half way up, looking down the incline:

Rusting incline wire rope:

Mid-levels winding house. Not in that good a nick:

This bit of graff from 1930 was interesting though:

Tower at the top of the main incline, standing proud still like some Welsh slate castle:

More pretty far-gone quarry buildings:

Smaller incline in the higher reaches of the quarry:

Reminds me of Mayan ruins in Mexico:

Cwm Machno quarry (also known as Cwm Penmachno Quarry) is located to the south-west of Betws-y-coed, at the head of the valley of the Machno, a tributary of the Conwy river, in North Wales. The nineteenth-century slate quarry was worked between 1818 and 1962. Initially slate was extracted in an ad-hoc manner by the locals but in 1849, serious development took place to allow wholesale extraction of slate.

Early O/S map of the quarry workings:

Slate was worked from an open quarry on several levels, and, additionally, slate was also extracted from underground. There were originally two pits, the upper working was known as Rhiw Fachno and the lower one was the main Cwm Machno quarry. Adits led into the mountain from both pits to access the underground workings. Inclines were used to link the terraces and workshops of quarries. It was particularly noteworthy for its water-wheel that enabled both the lowering blocks to the mills as well as being able to draw blocks and rubble from the underground workings.

Transport was always a major issue. Initially, slate was taken by horse-and-cart to a wharf on the River Conwy at Trefriw. From the late 1830’s, it was carted south to Maentwrog via Cwm Teigl and on to the Afon Dwyryd to Porthmadog. Then, in 1868, the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) opened their line to Betws-y-Coed and from then onwards slate could be hauled there, however this was still a distance of 11 km over rough mountain roads. With the completion of the Rhiwbach tramway in 1863 this allowed some of the slate to be hauled up to Rhiwbach Quarry and taken out to Blaenau Ffestiniog via the tramway

The quarry also suffered from a lack of waste tipping space. Its height on the mountain meant it had a relatively restricted water supply, and on several occasions work stopped due to drought, including in 1891. The quarry became a major employer, with the workforce rising from 70 men in 1872 to 178 at its peak in 1898, before dropping 108 in 1937-8. A community developed around it with houses for the married workers along with barracks for those that were unmarried. Output peaked in 1869 with production of 8,000 tons. However, by 1890, this had dropped to just 2,260 tons.

View of Penmachno quarry circa 1875, showing the northern mill:

2. The Explore

This place tends to get overlooked, due to the close proximity of the underground delights of Rhiwbach slate mine and, of course, the many mines of nearby Blaenau Ffestiniog. However, having seen the sheer size of the waste tips on Google Maps, thought that this was well worth a morning’s hike. As it transpired, it was time well spent. The main incline was a sight to behold and there were some really nice winding houses too. So not as spectacular as its neighbours but well worth a look if you have the time. The road trip over to Penmachno from Blaenau is interesting too!

3. The Pictures

Retaining wall at the bottom of the quarry:

One of the few quarry buildings still standing:

And its resident:

Inclines to the right:

Bottom of the big incline:

The long miner’s path to the top:

Slate waste as far as the eye can see:

Some of the original piping:

Half way up, looking down the incline:

Rusting incline wire rope:

Mid-levels winding house. Not in that good a nick:

This bit of graff from 1930 was interesting though:

Tower at the top of the main incline, standing proud still like some Welsh slate castle:

More pretty far-gone quarry buildings:

Smaller incline in the higher reaches of the quarry:

Reminds me of Mayan ruins in Mexico: